(330) 876-1228

8507 Main StreetKinsman, OH 44428

(330) 876-1229

Huntington's disease is a devastating, fatal neurological illness with little means of treatment, but a new study in mice offers a glimmer of hope.

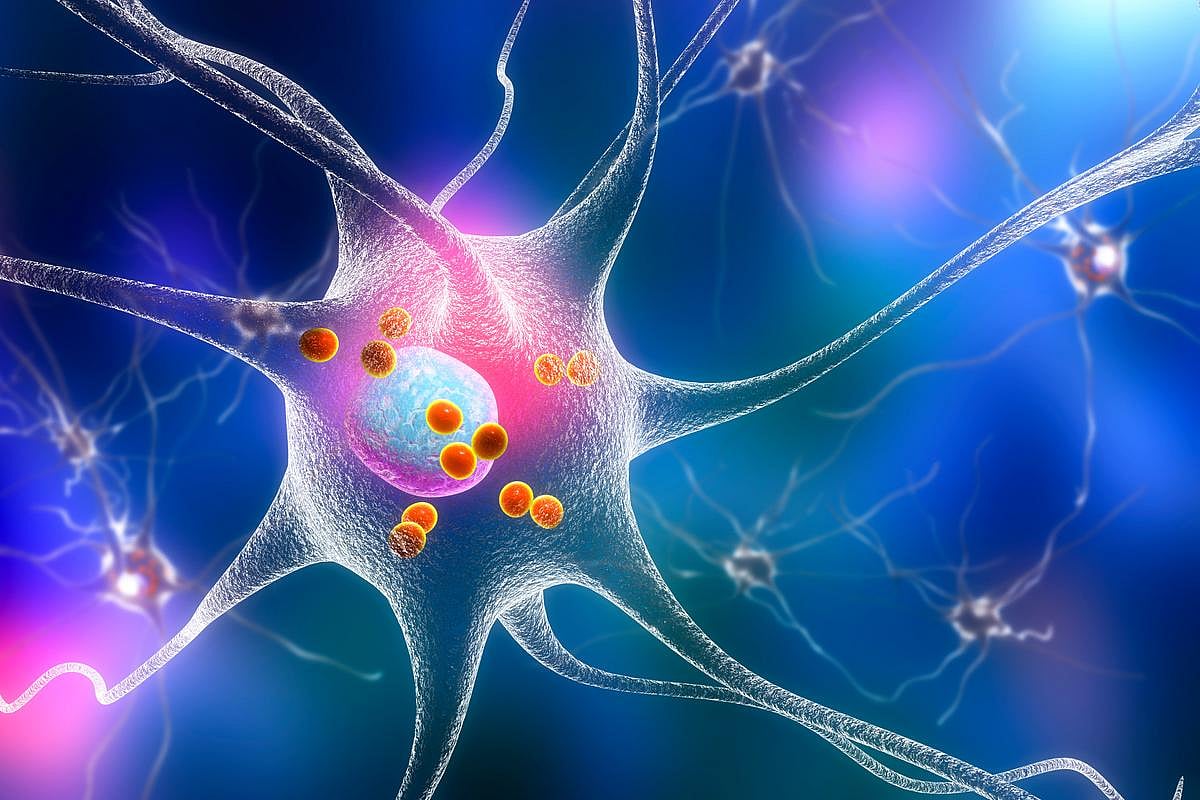

Huntington's occurs when inherited genes cause key proteins to fold and clump together within brain cells. Over time, this severely hampers brain function and patients lose the ability to talk, walk, swallow and focus. There's no cure, and the illness is typically fatal within a decade or two of symptom onset.

However, new research in mice is investigating the utility of "peptide-brush polymers" as treatment.

The peptides involved in the therapy are naturally occurring proteins that may block the lethal clumping of Huntington's-associated proteins within brain cells.

In studies conducted in a mouse model of Huntington's, use of the polymer treatment appeared to "rescue" brain cells harmed by protein clumping and reverse Huntington's symptoms, a joint team from Northwestern University and Case Western Reserve University reported.

Of course, studies in mice sometimes fail to deliver the same results in people.

Nevertheless, study co-lead author Nathan Gianneschi, of Northwestern University in Chicago, said "it’s quite compelling when you see animals behave more normally than they would otherwise" after the polymer treatment.

Gianneschi, a professor of chemistry at Northwestern, has a personal stake in the new research.

“My childhood friend was diagnosed with Huntington’s at age 18 through a genetic test,” he said in a university news release. “He’s now in an assisted living facility because he needs 24-hour, full-time care. I remain highly motivated -- both personally and scientifically -- to continue traveling down the path.”

The new findings were published Nov. 1 in the journal Science Advance and build on research conducted by a team at Case Western. The new study's co-lead investigator is Xin Qi, professor of brain sciences at Case Western.

In 2016, Qi's team first identified a protein called valosin-containing protein (VCP), which links up with the Huntington protein to cause the protein clumping that is at the heart of the disease.

As these clumps gather inside a brain cell's "energy factory," the mitchondria, this can lead to mitchondrial dysfunction and cell death.

However, “Qi’s team identified a peptide that comes from the mutant protein itself and basically controls the protein-protein interface,” Gianneschi explained. “That peptide inhibited mitochondrial death, so it showed promise.”

For various reasons, the peptide itself was tough to work with on its own as a treatment.

That's where Gianneschi's lab came in, developing a protective polymer that allowed the peptide to safely cross the blood-brain barrier and enter cells affected by Huntington's clumping.

In the mouse experiments, the rodents were injected with the polymer, which successfully infiltrated the brain. According to the news release, autopsied tissue showed that "the treatment prevented mitochondrial fragmentation to preserve the health of brain cells."

The therapy's success was also clear from changes in the animals' behavior.

“In one study, the mice are examined in an open field test,” Gianneschi said. “In the animals with Huntington’s, as the disease progresses, they stay along the edges of the box. Whereas normal animals cross back and forth to explore the space."

However, after the polymer therapy, "the treated animals with Huntington’s disease started to do the same thing," with behaviors returning to normal, Gianneschi said.

He noted that the treatment appeared to have no toxic side effects in the mice, another promising development.

“Huntington’s is a horrific, insidious disease,” Gianneschi said. “If you have this genetic mutation, you will get Huntington’s disease. It’s unavoidable; there’s no way out. There is no real treatment for stopping or reversing the disease, and there is no cure. These patients really need help."

The next step: "Optimizing" the polymer to get it ready for tests in people, and to also see if it might help fight other neurodegenerative illnesses, the research team said.

More information

Find out more about Huntington's disease at the Huntington's Disease Society of America.

SOURCE: Northwestern University, news release, Nov. 1, 2024